| LOST SADHANAS.ORG | THE LOST SADHANAS PROJECT |

The Vajra Dakini says,

This sadhana is specifically for retreats, when the meditator leaves the company of other practitioners, and seeks a more personal path towards liberation.

The practitioner will leave the monastery or household or shrine building and go out alone. It may be in the mountains, deserts, or jungle. The practitioner should find a sheltered place, a cave or rocky area or abandoned building, a place to stay for a specific period of time. The place must be clean of pollution, and the practitioner must purify it before entering. There should be a sleeping mat, enough food and water to last for the specified time, and a sacred object upon which to meditate. It would also be useful to have offerings.

This is a ritual that involves immanence rather than transcendence. The practitioner should enter meditation, seated and stable. He or she should become aware of being in two worlds at once, the paradise world and the physical world. He (or she) becomes a tree, like the Bodhi Tree, rooted in the earth. From his (or her) heart and mind come great branches, strong and curved at many angles. He is a tree that connects the worlds, and from his waist and hips come great thick roots that travel down deep into the earth.

The practitioner is a living connection between worlds. No mantras or mandalas are needed [at this stage]. The leaves and flowers open to great celestial light, and the environment is transformed.

The practitioner is no longer in a cave. The walls have become leaves and flowers, made of living light. There are singing birds, and lakes, and shrines with calling bells.

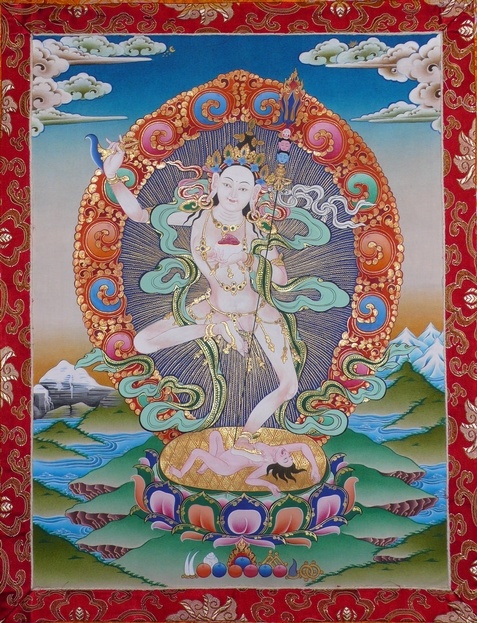

In the center of the paradise, I sit in peaceful form upon a white lotus throne. There are sparkling fountains, and warm winds with perfumes and flower petals.

At my feet are great rivers of souls, all seeking freedom from the passions and ignorance of physical life. They are advanced enough to have made it to the paradise but they are not ready to be reborn in a celestial form. I send the light of compassion into the waters and their hearts open with song. Layers of delusion are stripped away and they will return inspired to help others, to learn and teach.

The mind of the practitioner is the mind of the paradise. He realizes that all of it is conscious, and all is an extension of the compassionate mind of the Vajra Dakini. This is a world of infinite beauty and compassion.

There may be a second part to this meditation for those who choose it.At the base of the lotus throne is a double vajra, elaborately carved in shining silver. The practitioner finds it magnetic. He cannot turn his mind away from it. It spins and dissolves the paradise. It opens into the region of the ice caves.

It shines in the air, and it is reflected into infinite mirrors within the stalactites of ice. It is a place of purification. Ice knives strip away attachment and identity, the vajra's brilliance which remains is beyond ideas and forms. Here I am brilliant dazzling light before I descend into the realms of form.

The ice cave is the realm of the mind rather than the heart. Much of the Vajrayana tradition has chosen this aspect, rather than focusing on its celestial Mahayana roots.

The ice cave includes a path of asceticism and spiritual violence. Here we see no fragrant flowers or warm winds. Instead there are fierce winds, and the cold and ice create weapons for both self-defense and stripping away parts of the self. It is a vajra cave of sacrifice.

Here the doors are locked and guarded, for no young soul should enter by accident. The practitioner must have secret formulas, the mantras and mandalas to enter by force. No Buddha will encourage the stripping away of the ego identity, for it is painful.

If the practitioner requests entrance, it may be refused. If he fights his way in with empowered spells and objects, there are guardians who can deal with him.

But if he is humble, the veil is lifted and he is given the opportunity to build a pathway inwards. Here his initiation mandala is opened, and turned from a picture into a door. It moves in and out like an old-style accordion, moving from 2-D to 3-D, and later to multiple dimensions.

Mantras move the various parts of the mandala, and it opens like a safe with a complex combination lock. Each number of the combination is a Sanskrit mantra.

The initiatory mandala is like a safe, but when it is opened, there are more safes inside. The practitioner must work with mandala after mandala, remembering the proper order of mantras as keys, and mandalas as locks.

There are also skeleton keys, HRIM and SHRIM, which can loosen all tight mandalas.

Spinning the central mandala, like a great wheel at a bank vault, the mandala blossoms and the last door opens.

At this central entrance, the practitioner has a choice as to where to go. There are tunnels to siddhis (or supernatural powers) and great walkways of bodhisattva instruction. There are fountains of knowledge and forgetfulness. Then there is the mysterious path to liberation. The practitioner must choose wisely.

The ice caves are guarded by fierce protectors because they are dangerous. There is treasure there, supernatural insights and abilities, but what is most important is that the innocent visitor is not harmed.

One does not get powers for nothing. Parts of the self are stripped away, for the path to liberation requires sacrifice. This should always be voluntary.

The ice cave is like a train station, with trains leaving for different goals. But you must purchase the ticket with a piece of your heart, with your love of food or friendship, your enjoyment of sensuality or celebration. Pleasure is traded for power, and friendship is traded for a place in the hierarchy of Buddhist lineages.

The practitioner is not beyond competition here. Vajra weapons should be shined and honed, and mandala shields should be tested for weaknesses. It is a marketplace of gain and loss.

Each path has a question: "What do you want to gain, and what are you willing to give up for it?" The practitioner should know the answers to these questions before he enters.

I can be a guide in this realm, but usually I choose not to do so. Though many mandalas portray me as wrathful, I prefer my peaceful Mahayana forms.

There are guides who fit well, Vajrasattva for the more mature, Vajra Yogini for the more passionate, Vajra Krodha for the angry, and Vajrapani for those full of hatred.

I am willing to work with those who seek liberation, and are not tempted by other goals. But these seekers are rare.

More common are those who say they want liberation, but if given a chance will seek status or power. These may be justified (if these are gained, then the person can accomplish more good), but these are only empty justifications. This is the main reason why engaged Buddhism is often the opposite of liberation.

The bodhisattva gives up individual status, and becomes a channel for the compassion of the universe. The magician, however, keeps both ego and knowledge, and learns to manipulate the pranas or cosmic worlds. There is much to learn in the ice caves.

This concludes one set of sadhanas provided by the Vajra Dakini.The next set of sadhanas involves spiritual guidance from the Vajra Dakini in her seven bird-headed forms.

Please click on the [ NEXT ] link below to continue.

[ BACK ] The Diamond Land Meditation [ NEXT ] The Vajra Dakini - Introduction to the Sadhanas of the Bird-Headed Dakini

Introduction | Methodology - Participant/Observer | The Bodhi Tree Sadhanas | Vajra Dakini Discussion | Vajra Dakini Commentary | Vajra Dakini Sadhanas | Vajra Yogini Commentary | Maitreya Sadhanas | Vajradhara Speaks About Yidams | Lost Sadhanas Conclusion

Home

Copyright © 2021, J. Denosky, All Rights Reserved